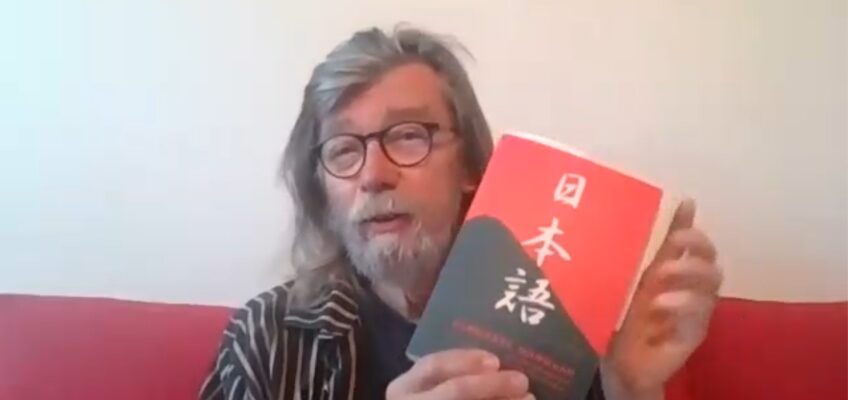

「『短歌から漫画へ』ー どのように日本の言語と文化をフィンランド語に翻訳するか」という本を読みました。

私は日本の同僚に、おそらく日本で不適切なことをするようアドバイスしていたことに気づきました。

「一人称で話すことで、誰が誰と何をするのかを正確に示す」ことを対話トレーニングで強調しました。 しかし、自分自身について繰り返し言及するのは子供じみており、自分自身のエゴを強調するのは洗練されていないと考えられていると、この翻訳に関する本は指摘しています。

日本では物事がただ起こる傾向があり、人は能動的な主体というよりむしろ受動的な対象と捉えられているようです。

この背後には、(地震と台風の多い国で)大災害に直面した謙虚さに加えて、自己を強調することは悪いことであるという日本の礼儀作法に固有の謙虚さもあります。

言語学者によると、英語(フィンランド語も同様)は「DO-LANGUAGE」(する・言語)です。一方、日本語は「BECOME-LANGUAGE」(なる・言語)です。何かが現れ、生成します。 フィンランドの読者にとって、登場人物の性別や社会的地位などは必ず付記されるべきものですが、日本人にとっては、これらはすべて文脈や発言の丁寧さによって理解できると捉えられています。(もし私が平均的な日本人と同じように文脈を読むことができたら、私は注目すべき社会科学者になっているでしょう!)

私の理解が正しければ、自分自身について言及しないことは、社会的状況において調和を保つことに重要です。そして日本においては調和が重要な価値観です。どのように調和と対話性を同時に重視したらよいでしょうか? Open Harmony(開かれた調和)のようなものはあるでしょうか?日本の対話空間は、開かれた調和の場となり得るでしょうか、と私は考えました。 その答えは文化と文脈を知っている日本の同僚によって、そして対話の中で良い経験として見つけられることでしょう。

社会人類学者のレナト・ロサルドは、1989年の著書『文化と真実 ー 社会分析の指摘』で次のように書いています。「どんなに努力しても外国の文化を現地人の人々がやっているように理解できるようにはなりません。」

とはいえ、異なった文化が出会う時に出現する「文化的境界地」では、自分の文化をより理解できることを学ぶユニークなチャンスを得ることができるでしょう。あなたは普遍的である思っていたことが特殊であり、自明であった事も自明でない、ということが明らかになります。対話性の力 ー 聴かれること、発声すること は、あらゆる文化で人の心を打つようです。

それぞれの文脈に適し、そして文化的にセンシティブなアプローチとは?

– このことが、私が「文化的境界地」についてもっと知りたいと思っていることです。

同僚と対話し、ローカルな文脈で対話の場を生成すること。 DPIウェビナーはその道への素晴らしい一歩であり、私をとても幸せにしてくれました。

(ダイアローグ実践研究所 理事 片岡豊 訳)

Tom wants to know about ‘cultural borderlands’.

Reading a book called “FROM TANKA TO MANGA. How to translate Japanese language & culture into Finnish” I realized I had advised Japanese colleagues to do things perhaps not appropriate in Japan. ‘Talk in the first person, indicate precisely who does what and with whom’ the dialogue training emphasized. Repeated referring to oneself is, however, considered childish, the book on translating points out, an emphasis on one’s own ego is considered unsophisticated, And in Japanese things tend to just happen, persons are rather passive objects than active subjects. Behind this is, besides humility in the face of the great cataclysms (in a land of earthquakes and typhoons), also modesty inherent in the Japanese etiquette where emphasizing self is bad behavior. According to linguists, English (as well as Finnish) is “DO-LANGUAGE”: Someone does something, Japanese, on the other hand, is “BECOME-LANGUAGE”: Something emerges or generates. For Finnish readers things like the gender or social status of the characters have to be added somehow, for Japanese people, all this can be understood by the context, the politeness of utterances and so on. (If I could read contexts like the average Japanese person, I would be a remarkable social scientist!)

Refraining from referring to oneself is, if I understand correctly, also important in keeping up harmony in social situations – and harmony is an important value in Japan. How to cherish harmony and dialogicity at the same time? Could there be something like Open Harmony, I thought, could Japanese dialogical spaces be spaces of open harmony? The answers could obviously be found by Japanese colleagues who know the culture and context – and in dialogue about good experiences.

The social anthropologist Renato Rosaldo wrote in his 1989 book ”Culture and Truth: The Remaking of Social Analysis” that no matter how you try, you will not learn to understand a foreign culture the way locals do. You will, however, have unique chances of learning to understand more about your own culture in the “cultural border-lands” that emerge when cultures meet. Things you thought are universal turn out to be particular, self-evident matters prove not to be self-evident. The power of dialogicity – of being heard and having a voice – seems to touch hearts in all cultures. What are the appropriate, culturally sensitive approaches in each context – this is something I very much would want to learn more about, in “cultural border-lands”, dialoguing with colleagues generating dialogical spaces in their local contexts. The DPI webinar was a delightful step down that path and made me very happy.